Vital checks for illegal meat at the Port of Dover might have to cease within seven weeks, if the Dover Port Health Authority (DPHA) does not receive an adequate funding settlement from Defra.

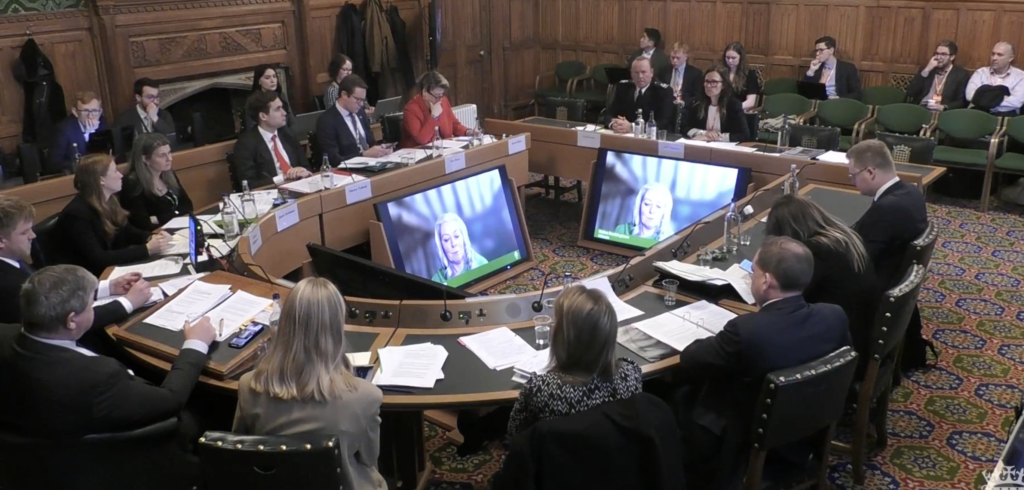

The warning was issued by Lucy Manzano, DPHA’s head of port health and public protection, in a highly revealing evidence session in front of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee, during which she laid bare the deep flaws in the UK’s border controls.

This included the revelation that meat and dairy products from Germany continued to enter the UK unchecked for days after the foot-and-mouth ban came in.

Funding shortfall

Throughout the session, Ms Manzano reiterated how DPHA was the lead body in seizing illegal meat brought in through Dover, in contrast to Defra’s repeated claims that this work is led by Border Force.

Out of around 71 tonnes of meat seized in a year, DPHA was responsible for nearly 69t, she said. Yet this work, carried out in incredibly difficult conditions in the ‘live lanes’ at the port, may have to stop soon because funding has not been provided for the 2025/26 financial year, she said.

The previous government slashed funding for the work for 2024/25 and reduced it to nothing for the next financial year. This is partly linked to the cost of running the new Border Target Operating Model for commercial meat import checks.

Currently DPHA operates at around 20% coverage due to financial constraints, but has still managed to seize 170t of illegal meat since September 2022.

Ms Manzano said DPHA, as requested, had submitted funding models to Defra ranging from £6m for 50% coverage, which also cover Coquelles, the Eurotunnel entry point n the French side, to 100% coverage.

But she told the MPs there had been ‘no substantive response’ from the department. “There are significant gaps in the controls that are taking place. Defra is not communicating regarding the intelligence or understanding of what’s actually happening on the ground, which is fairly fundamental in this,” she said.

“If our funding is not secured, certainly within the next seven weeks, coming into year-end, these checks will stop because the local authorities are not in a position to fund them.”

She stressed that while DPHA works closely with Border Force on the ground, it is DPHA doing the ‘complex’ work of seizing the meat.

“Put simply, Border Force has the powers to stop, we are taking the action, which is immensely complex. If we are not at the port, the seizures are not taking place and the vehicles will be put to one side until we are there to process them. That is the operational reality at the Port of Dover,” Ms Manzano said, before revealing that, in the first two days of February, the DPHA team removed almost 4t of illegal meat.

“If we’re not there, this stuff is going out on the shelves. This is not stuff where, traditionally, it would be hard to get hold of – this stuff is appearing in shops on high streets and in markets. You may well be going out for dinner in normal looking establishments and be consuming meat that has not been correctly processed.”

Organised crime

She highlighted how organised the crime was, often targeting the UK with pork products from places like Romania where African swine fever (ASF) is rife and exports should be banned.

It enters the country in vans or even coaches without passengers but packed with meat. The only sanction when they are caught is the seizure of the meat, meaning there is very little deterrent.

Also appearing in front of the committee, David Smith, Border Force’s, south east regional director, who said that his organisation plays a big role alongside DPHA in tackling illegal meat imports but acknowledged that DPHA had the primary role in seizing illegal product.

“We work in very close collaboration with our colleagues in Dover and around the country to do as much as we can in this space with the resources we have available to do what we can do,” he said.

He said Border Force was ‘always on duty 24-7’ and will always deal with illegal POAO, if detected. Mr Smith said that if DPHA is not available for a short time, it will hold products for itto process, but added that if DPHA is not available for longer, Border Force will process and seize the meat. “We do not ignore detections of illegal meat – I need to be really clear about that,” he said.

He suggested that Border Force would also benefit in this work from more funding, but insisted its work on illegal meat is a high priority, alongside drugs and weapons, for example.

“This is fundamentally a very resource-intensive activity. We are talking about huge quantities of meat that need to be detained, prrocessed, bagged, tagged and we have to get rid of it in a safe and secure manner. So, of course, more resources of any kind, whether that’s Border Force resource or my colleagues from port health, would be welcome in dealing with the volumes we are currently seeing,” Mr Smith said.

BTOM concerns

Ms Manzano also highlighted the deep flaws in the government’s Border Target Operating Model (BTOM) that are allowing commercial meat imports to enter the country unchecked in large volumes, and mean criminal gangs are easily able to target the UK.

These include the decision not to process checks at the point of entry at Bastion Point in Dover, a readily-available border control post, but to do so 22 miles inland at the new BCP at Sevington. This means vehicles that have been requested to present at Sevington for inspection can simply choose not to go or unload their vehicles first, while, in some cases, notifications are coming through too late.

Ms Manzano said that decision was ‘not based on biosecurity and stressed that ‘the very purpose of import controls is to keep the bad stuff out and contain it at first point of entry’.

Ms Manzano said Defra had failed to provide ‘any confirmation of how food would be controlled at the point it arrives, or more importantly, between the point it arrives and the inspection facility that is accessed 22 miles across’.

She said very few checks were taking place at Sevington under the-risk-based system, with many consignments being auto-cleared under the ‘timed-out decision contingency feature’ (TODCOF) system.

This was introduced under the BTOM to help avoid delays at the new border control post at Sevington. It allows loads to auto-clear via a digital system two hours prior to arrival to avoid inspection, provided they have self-declared as being ‘low risk’.

“Defra has continually stated that there are robust controls in place. There are not. They don’t exist and they have overstated the activities of Border Force at the border to identify commercial goods,” she said.

She said DPHA had stressed to Defra and the Food Standards Agency that the system is ‘not working and we have to action change’.

Lack of communication

Ms Manzano also repeatedly highlighted the lack of communication and direct contact from Defra, for example in responding to the FMD outbreak, regarding what is happening at the front line.

She suggested this had been the case for a few years – for example, no ministers have visited Bastion Point in Dover to see at first hand the work there in seizing illegal meat imports.

At one point EFRA chair Alistair Carmichael suggested Defra wasn’t speaking to DPHA because ‘they might hear things they don’t want to’. Ms Manzano readily agreed.

A Defra spokesperson said the UK has strict import controls in place to manage the risk of ASF and works closely with port health authorities and Border Force to ‘ensure our robust border controls are enforced’.

Inland ‘debris’

Helen Buckingham, an Environmental Health Practitioner and regulatory consultant, said she is often contacted by inland authorities, who are having to ‘pick up the debris’ being let through the UK’s various points of entry, but said Defra appeared to be unaware of this wider impact of the border failings.

“There are a lot of players in this space with a lot of distinct responsibilities in a very complicated landscape. Therefore in this context, inter-agency working needs to be incredibly united and robust,” she said.

“My colleagues would say there is an extreme lack of understanding about the enforcement delivery on the front-line – the people that are writing the rules are not asking us to help them write it, to help them shape it and to make it workable and that’s where there’s been a real breakdown in communication between national level and what’s happening on the ground.

“The inland local authorities are running around picking up all this debris up when it lands, either from the illegal personal route or from failed SPS checks.

“But their work isn’t being counted and they have no means of sharing intelligence with each other – and, that for me, is a real breakdown in this network. It could be so much better.”

As well as the huge risk to UK livestock from disease like FMD and ASF, the human health implications of the flawed controls were discussed. Ms Buckingham also highlighted the risk of zoonotic diseases, which can pass from animals to humans, being allowed into the country.