Wilfred Emmanuel-Jones, better known as the Black Farmer, delivered some hard-hitting messages when he addressed the NPA Producer Group. Alistair Driver reports

The Black Farmer has an extraordinary story to tell – and he is now urging others within the pig industry to open up and tell theirs.

Invited to speak to the NPA’s latest Producer Group meeting about marketing pork, Wilfred Emmanuel-Jones delivered one of the most colourful, unrestrained and frank presentations the group had heard in some time.

An extrovert with a flair for marketing, he used his experience to highlight what he sees as the pig industry’s failure to engage effectively with the consumer and to encourage a change of mindset.

“People buy people, not the product,” was the core message as he challenged the industry to find ‘champions’ to reach out ‘with authenticity and passion’ to consumers beyond supermarket own brands and industry labels.

Early life and career

Mr Emmanuel-Jones was born in Jamaica and moved with his family to England as a child in 1961. He grew up in Small Heath, in Birmingham, as one of nine children living in a small terrace house – and at the age of 11 he decided he wanted to be a farmer.

Mr Emmanuel-Jones was born in Jamaica and moved with his family to England as a child in 1961. He grew up in Small Heath, in Birmingham, as one of nine children living in a small terrace house – and at the age of 11 he decided he wanted to be a farmer.

Having struggled with dyslexia, he left school at 16 without qualifications and joined the army, but, a self-confessed ‘stroppy black kid’, was soon kicked out.

Instead, he got a job in catering and ‘really took to being a chef’. But, driven by his desire to raise enough money to buy a farm, he decided that he wanted to break into television. It took two years of persistence before getting his break with a three-month contract at the BBC, which started a successful 15-year career as a producer and director, including working on the Food and Drink Programme.

But still not satisfied, he left television to set up his own food and drink marketing agency, focusing on ‘challenger brands, which were totally different’, such as Loyd Grossman sauces,, Kettle chips, Cobra beer and Plymouth Gin. None of the brands had any money, but succeeded through ‘below the line marketing’, driven by the internet revolution, social media and word-of-mouth.

That finally gave him enough money, at the age of around 40 in the late-1990s, to buy a 30-acre farm on the Devon-Cornwall border. “The first thing I noticed is that there is a massive divide between urban and rural Britain,” he said. “They don’t understand each other. Also, the farming industry is very insular and very conservative. The people who do all the goddamn work have no connection with the people buying the product. And I saw an opportunity.”

The Black Farmer

Opting to create a sausage brand, he found a manufacturer but needed a name. “It came to me. One of my next-door neighbours used to call me the ‘Black Farmer’. It has an edge to it – people are not sure if it is politically correct. You need to create intrigue,” he said.

He knew nothing about pigs, but was taught the basics by local pig producer Andrew Freemantle, who, in the room as a member of PG, was thanked by Mr Emmanuel-Jones for ‘going out of his way to help’.

The supermarkets were not interested in the Black Farmer’s products, however, so using his marketing experience, he embarked on a ‘below the line’ marketing campaign utilising the digital revolution to the full. This included a ‘massive sampling programme around the country’ – he asked people who took part to go onto supermarket websites to enquire why they weren’t stocking the Black Farmer’s product.

Eventually it worked and the brand has grown to become one of the best known food brands in the country, now encompassing a wide range of products and attributes for consumers (see below).

“You need to galvanise the consumer, and everything I do, I make sure I look after the consumer and make the consumer feel involved,” he said.

“If there is one this industry is rubbish at, it is galvanising the consumer,” he said, accusing the sector of being more concerned about industry politics than reaching out to consumers.

The Black Farmer has, himself, crossed swords with the NPA in recent months over claims he made about antibiotic use in the pig industry when launching his ‘Raised Without Antibiotics’ label. The brief spat didn’t concern him – in fact, he welcomed the fact that it got people talking about him.

Questioned about the potential for marketing pork products to promote one system over another amid the unwelcome spotlight of animal welfare activists and other industry critics, he accused the industry of too being timid and reactive.

“People are on the defensive, they are concerned about a reaction and that is holding the industry back. It doesn’t matter what you do – you are always going to be criticised,” he said.

PG members challenged Mr Emmanuel-Jones, who doesn’t produce his own pigs, on how relevant his philosophy was to the wider industry. As Mr Freemantle pointed out, most producers are focused primarily on sending a quality product to the abattoir. Many don’t have the time or resource to market their own goods.

Mr Emmanuel-Jones insisted pig producers should not be satisfied simply to have produced a high quality product and shouldn’t rely on retail own brands, bodies like AHDB or the Red Tractor label – which he said ‘means a lot to the trade but nothing to the consumer’ – to communicate its value to consumers.

“You start from the basis that it is a fantastic product and then the work starts. People buy my product because of what I stand for – they feel part of something.”

Connect with people

The key to marketing is to connect with people ‘so they become your disciples, your messengers and champion your cause’, he said.. He told the group the public’s image of pig farmers was ‘outdated’ and very different to what he could see in the room.

The key to marketing is to connect with people ‘so they become your disciples, your messengers and champion your cause’, he said.. He told the group the public’s image of pig farmers was ‘outdated’ and very different to what he could see in the room.

Identifying individuals, he urged them to become an ‘industry face and go and shout about British pork’. “Don’t use celebrities. Create your own champion to sell the passion in this industry. There is an authenticity and truth to this group,” he said.

NPA chief executive Zoe Davies asked how farmers who sell large volumes for retail labels could break away from being ‘standard pork producers’.

His advice was to maintain the contract, but hold some product back to create your own brand. The key is to think ahead and not be restricted by current tastes and to try and find something different and unexpected. Working with ‘innovators’, such as chefs, can help build a brand, he said.

“Always start small and with an area you already know well,” he advised, adding that there was currently a very strong interest at home and abroad in ‘Britishness’, regardless of method of production.

“There’s lot of goodwill and a lot of good things you are doing, but you are not shouting about it.

“People buy people. That is fundamentally what you have to understand. People don’t buy the product, they buy you.”

PG members didn’t necessarily agree with all he said, but no-one could question the drive and passion behind one of British pork’s most successful brands and some of the fundamental truths in his message.

The Black Farmer brand

The brand promises ‘flavours without frontiers’.

The brand promises ‘flavours without frontiers’.- Ranges include Raised Without Antibiotics pork products; Gluten-Free and Reduced Fat sausages alongside other sausage flavours; Hickory Smoked Back bacon; organic, free-range and corn-fed chicken; Protein Plus eggs; beef and pork meatballs; burgers and Sweet Mature cheddar. Much of the meat is RSPCA Assured.

- Plans are in place to launch tea, coffee and more beef products.

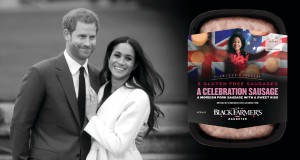

- The Black Farmer is marking May’s royal wedding by launching a special edition sausage celebrating the mixed heritage of his daughter and Meghan Markle.

- Products are available in Sainsbury’s, Waitrose, Ocado, Asda, Budgens, Iceland and Morrisons.

- See http://theblackfarmer.com

The Hatchery

Wilfred Emmanuel-Jones recently announced the launch of ‘The Hatchery’, which will support ‘ambitious food entrepreneurs’ in developing their brands.

Wilfred Emmanuel-Jones recently announced the launch of ‘The Hatchery’, which will support ‘ambitious food entrepreneurs’ in developing their brands.

The Black Farmer will mentor the businesses, ensuring they benefit from some of the advantages that large businesses take for granted – knowledge, reputation, scale and financial resources.

Nine out of 10 new businesses fail in their first three years, but most of the pitfalls that scupper new brands are avoidable, he said.

“The key to beating the large, soulless corporate brands and the bland supermarket own-labels is to create a brand with personality – a brand that makes you feel something,” he added.